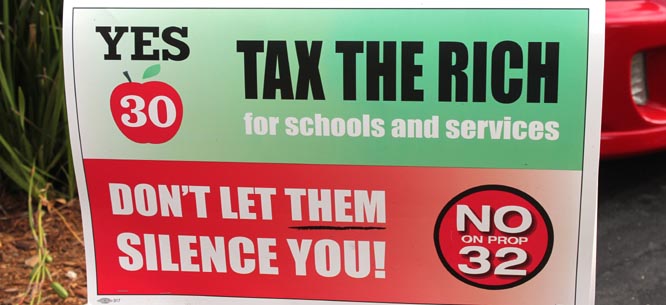

Photo of California Prop 30 campaign banner by Quinn Dombrowski, via Wikimedia Commons

Barack Obama’s K-12 “reform” policies have brought misery to public schools across the country: more standardized testing, faulty evaluations for teachers based on student test scores, more public schools shut down rather than improved, more privately managed and for-profit charter schools soaking up tax dollars but providing little improvement, more money wasted on unproven computer-based instruction, and more opportunities for private foundations to steer public policy. Obama’s agenda has also fortified a crazy-quilt political coalition on education that stretches from centrist ed-reform functionaries to conservatives aiming to undermine unions and privatize public schools to right-wingers seeking tax dollars for religious charters. Mitt Romney’s education program was worse in only one significant way: Romney also supported vouchers that allow parents to take their per-child public-education funding to private schools, including religious schools.

After the November 6 elections, public school supporters speculated about (hoped for) a change in direction in Obama’s second term. Unfortunately, there’s no reason to expect a shift. By the time Obama launched his first presidential campaign in 2007, he had embraced reform-think. His longtime basketball buddy, über-reformer Arne Duncan, undoubtedly influenced his views. The two met on the court more than twenty years ago. Once Duncan took over as CEO of Chicago Public Schools in 2001, he became Obama’s sounding board on education policy and escort on school visits. It made perfect sense from Obama’s perspective to appoint Duncan Secretary of Education in 2008. And the administration’s signature education program, Race to the Top, perfectly embodies reform-think: it gives states (all of them resource-starved) a chance to compete for grants only if they pledge to adopt a full reform program.

Rumors that Obama might replace Duncan with ultra-extreme reformer Michelle Rhee caused some panic but needn’t have. Obama and Duncan are a team. Duncan announced his desire to stay for a second term in September 2012. Just ten days after the election, in prepared remarks to the Council of Chief State School Officers, he stated that his department’s second-term job would be “to support the bold and transformational reforms at the state and local level that so many of you have pursued during the last four years.” There was also talk that Obama-Duncan might focus more on preschool and higher education, both less controversial than their K-12 agenda. But even if this does pan out, Race to the Top has given the administration’s suite of ill-conceived reforms a life of its own. As seen on election night and as indicated in Duncan’s speech, the main action has moved to the state and local arenas.

The rescue of public education must come from the grassroots, from a coalition led by parents and teachers. Such a movement has been taking shape gradually and gained visibility during the 2012 election cycle. The number of education-related campaigns has increased as ed reformers try to entrench their policies in law. In addition to the familiar battles over school funding, there are votes on charter schools, the content of teacher contracts, vouchers, and union rights (the four largest unions in the United States represent teachers and other public sector workers). Disregarded in the past, elections for school boards and superintendents have become major battles. This year’s education votes were high-profile within individual states, fiercely fought, and outlandishly expensive; some attracted national attention. Public education supporters won some impressive victories and suffered several bitter disappointments. Here is a review of some pivotal votes, who supported what, and why:

Alabama: Voters defeated Amendment 4 (64.6 to 35.4 percent)*, which would have deleted from the 1901 state constitution language that validated the poll tax and school segregation by race. Counterintuitively, opposition to the amendment came from black leaders, the state teachers union, and Democrats because it left intact this clause: “…nothing in this Constitution shall be construed as creating or recognizing any right to education or training at public expense….” The language was inserted in 1956 to enable the state to dismantle public education rather than integrate schools. Business groups interested in limiting public expenditure on education supported the amendment. Opponents argued that eliminating the racist language but leaving the no-right-to-public-education clause effectively legitimated the latter, putting public education at risk. The amendment as written, they argued, would change nothing in practice for the black community since federal law prohibits de jure school segregation and poll taxes.

*All the results reported here are final figures or the latest available as of November 19, 2012.

Arizona: Voters defeated Proposition 204 (58 to 42 percent), which would have made permanent a 2010 one-cent sales tax to fund education, vocational training, and college scholarships.

Voters approved Proposition 118 (54.9 to 45.1 percent), which creates a more stable source of revenue for public education by changing the formula for distributing the earnings of a state trust fund until 2021. The money in the trust fund comes from the sale and lease of state lands. The Arizona Education Association, the state’s main teachers union, supported the proposition.

California: Voters approved Proposition 30 (54.7 to 45.3 percent), a constitutional amendment to raise income taxes by 1 to 3 percent on incomes over $250,000 for the next seven years and the sales tax by a quarter cent for four years to fund public schools and universities. Overcoming public aversion to tax increases in favor of public education marks a milestone in recent California history; higher taxes are also the only way to deal with the crisis in state education funding.

Voters defeated Proposition 32 (56.4 to 43.6 percent), which would have prevented unions from deducting political contributions from employee paychecks. This is a crucial win for the labor movement.

Voters defeated Proposition 38 (72.2 to 27.8 percent), a second tax increase for funding public schools and early childhood programs that competed with Proposition 30. Prop. 38, a state statute, would have raised everyone’s income taxes on a sliding scale for twelve years and allocated 30 percent of the revenue to repaying state debt for four years. Molly Munger—a wealthy Los Angeles lawyer and public education advocate—provided the impetus for the measure and more than $44 million of the nearly $48 million raised for the campaign. Munger came under strong pressure to withdraw Prop. 38 because both polls and conventional wisdom held that two tax increase propositions for education would split the yes vote, and both would lose. The California State Parent Teacher Association supported Prop. 38. Prop. 30 had much broader support, including Governor Jerry Brown, the Democratic Party, and the major unions.

Colorado: Denver voters approved Ballot Issue 3A (69 to 31 percent), a property tax increase that will raise $49 million for early childhood education and “enrichment programs” such as art, music, and physical education (these were once considered an integral part of a standard curriculum). Voters also approved Ballot Issue 3B (63.5 to 36.5 percent), a bond issue to raise $466 million for facility maintenance, renovations, and four new schools. Jeannie Kaplan, a Denver Board of Education member who opposes the in-vogue reform agenda, endorsed the ballot issues only after ensuring there would be public accountability and due consideration for opening new district-run schools and not just charters. The Denver Classroom Teachers Association contributed $13,000 to support the ballot issues. Michael Bloomberg—New York City mayor, multibillionaire, and nationwide ed-reform financier—gave $75,000. This was a rare instance when Bloomberg and a teachers union found themselves on the same side.

Connecticut: Voters in Bridgeport defeated a charter revision (53.3 to 46.7 percent) that would have replaced the elected Board of Education with one appointed by the mayor. The Democrats, including the mayor, supported the charter revision. Michael Bloomberg, who exercises “mayoral control” over NYC’s schools, contributed $20,000 to the charter revision. The pro-labor, left-liberal Working Families Party led the campaign against it and also won three seats on the board.

Florida: Voters defeated Amendment 8 (55.5 to 44.5 percent), which would have repealed the constitutional ban on public funding for a religion or religious institution. The amendment would have cleared the way for a statewide voucher system. Under a statewide voucher system, every child receives the same sum and can apply to any school; schools compete for the money. In a 1955 article called “The Role of Government in Education,” free-market proselytizer Milton Friedman proposed vouchers as the best way to provide K-12 education in a democracy. Only the private market, he argued, can provide quality goods efficiently at the best price for consumers, but there might not be a market incentive to educate every child; since the state has an interest in a literate citizenry, the government would provide a voucher to every child to be used at any accredited school. Such a system unavoidably exacerbates inequalities: the price of sought-after schools rises above the value of the voucher; wealthy parents don’t need vouchers but get them anyway; middle-class parents supplement the voucher with whatever they can afford, driving up prices. As Friedman admitted, there might not be an incentive for “sellers” to provide enough voucher-priced schools. In that case, the government would run schools for whomever couldn’t afford to shop in the market. The goal of many conservative ed-reformers is a system like Friedman’s.

Georgia: Voters approved constitutional Amendment One (58.6 to 41.4 percent) to allow the state government to accept charter school applications, bypassing local school districts. Until the vote, local school boards reviewed applications, and applicants could appeal rejections to the State Board of Education. The amendment authorizes a new type of school: state charter schools. The campaign turned into a cause célèbre for charter proponents, who raised over $2 million to support the amendment. They included Arkansas Wal-Mart heiress and Walton Family Foundation board member Alice Walton ($600,000), Michelle Rhee’s StudentsFirst ($250,000), Home Depot co-founder Bernie Marcus ($250,000), the Virginia-based cyber school company K12 ($100,000), charter school operator J.C. Huizenga ($75,000), and Florida-based for-profit school operator Charter Schools USA ($50,000). The out-of-state money overwhelmed opponents of the amendment; they raised only $123,243, mostly from Georgia public school officials.

Another wrinkle in the Georgia amendment story is the wording on the ballot: “Shall the Constitution of Georgia be amended to allow state or local approval of public charter schools upon the request of local communities? YES ( ) NO ( ).” This obfuscates what the amendment does. Citizens could find the full text of the amendment—dense language that revises three paragraphs in two different sections of Article VIII—on the Secretary of State’s website or at the offices of county probate courts. Summaries were published in the “official legal organ” of each county. Not surprisingly, most voters relied on the ballot language, and some were angry about being misled. There’s no likely recourse: the politicians in power (in this case, Republicans) control the wording, and Georgia’s courts have refused to review ballot language. Had the intent of the amendment been described clearly on the ballot, it’s possible that voters would have said no—not necessarily because they dislike charter schools but because they wanted decision-making to remain in the districts where they live.

Idaho: Voters defeated Proposition 1 (57.29 to 42.71 percent), which would have phased out renewable contracts for teachers, abolished formal review for anyone fired, allowed school boards to reduce the salaries of staff with renewable contracts without due process, limited collective bargaining to salaries and benefits, eliminated provisions for fact finding in professional negotiations, and more.

Voters defeated Proposition 2 (57.98 to 42.02 percent), which would have instituted a merit bonus program for teachers based on student scores on state-mandated tests, other measures of student performance, leadership, or taking a hard-to-fill position.

Voters defeated Proposition 3 (66.71 to 33.29 percent), which would have mandated two online courses for high-school graduation (a great boon to software companies) and shifted $14.8 million annually from teacher salaries to reform programs, including providing a laptop computer for every high-school student and teacher.

The propositions were actually a referendum on three laws passed in 2011, dubbed the “Luna Laws” after State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Luna. A total of $6.4 million was spent on the campaign. Proponents of the laws collected $2.8 million, including $1.6 million from conservative billionaire Frank VanderSloot, $250,000 from supermarket heir Joe Scott, $200,00 from NYC Mayor Michael Bloomberg, and $100,000 from Michelle Rhee’s StudentsFirst. Opponents raised even more—about $3.6 million, including $2.8 million from the National Education Association, the nation’s largest union and chief architect of the victory. The defeat of Proposition 3 automatically canceled the state’s $182-million contract with Hewlett-Packard Co., signed two weeks before the vote. The deal was yet another reform-generated corporate windfall: the state would have rented the computers and also paid for all loss, theft, and damage.

Indiana: Voters elected Democrat Glenda Ritz as Superintendent of Public Instruction over incumbent Republican Tony Bennett (53 to 47 percent). Bennett, a hero among ed reformers, implemented what is considered the most aggressive program in the nation. It includes every item on the reform agenda as well as the largest voucher program and the only one not limited to low-income students and students from low-performing schools. Allowing middle-class parents to take their per-child allotment of tax dollars to private schools speeds up privatization of the entire system. Bennett raised almost $1.7 million for his campaign, including contributions from Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton ($200,000), NYC Mayor Michael Bloomberg ($80,000), and Los Angeles billionaire Eli Broad, whose foundation trains ed-reform school administrators ($100,000).

Glenda Ritz—a veteran educator who achieved the highest teaching credential, National Board Certification—will be the first Democratic state superintendent in forty-two years. She raised $327,000, less than one-fifth of Bennett’s total. It was a stunning victory for critics of Indiana’s reforms, but immediately after the election, state Republican leaders claimed that nothing would change: they considered the vote a repudiation of Bennett, not his policies. “The consensus and the momentum for reform and change in Indiana is rock solid,” outgoing Governor Mitch Daniels said. Ritz’s difficulty will be dealing with the Indiana State Legislature: the Republicans have supermajorities in both houses. Meanwhile, Bennett is now on the short-list for Florida Commissioner of Education, an appointed position.

Michigan: Voters defeated Proposal 1 (52.7 to 47.3 percent) and thereby repealed a 2011 law (Public Act 4) that allowed the governor to appoint “emergency managers” to take control of financially distressed cities and school districts. Emergency managers had the power to scrap or amend collective bargaining agreements, change pension agreements, sell public assets, and enact and repeal laws. The primary funder of the repeal campaign was the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. At the time of the vote, three school districts, including Detroit’s, and five municipalities were under emergency management. This meant that over half of the state’s African-American population lived under the authority of an emergency manager or consent agreement (which grants emergency powers to local officials).

At the same time, Michigan voters defeated Proposal 2 (57.4 to 42.6 percent), a constitutional amendment that would have guaranteed public and private-sector employees the right to organize, bargain collectively, enforce agreements, and collect dues. This was a major defeat for labor. The mind-boggling cost of the campaign shows how much was at stake for the labor movement and its opponents. The unions raised about $23 million for the campaign. Opponents raised about $31 million, mostly through pro-business campaign groups. Immediately after the vote, Republicans began considering a right-to-work law to bar union membership or fee payments as a condition of employment. Once a union state par excellence, Michigan could become a right-to-work state.

Missouri: Voters defeated Proposition B (50.8 to 49.2 percent), which would have raised the excise tax on a pack of cigarettes from 17 cents (the lowest in the nation) to 90 cents. Fifty percent of the revenue would have gone to K-12 education, 30 percent to higher education, and 20 percent to curbing smoking. Proposal 2’s most prominent opponent was Ron Leone, head of the Missouri Petroleum Marketers and Convenience Store Association. Given the close vote and worries over cuts to the education budget, the tax will likely be on the ballot again.

Ohio: Cleveland voters approved Issue 107 (56.5 to 43.5 percent), which creates a new four-year property tax to improve the city’s schools. For the first time, local levy money will go to charter schools. The levy will bring in a maximum of $85 million annually (the city currently has a 79 percent collection rate) with $5.7 million going to charter schools that partner with the school district. The Ohio Federation of Teachers fought the charter share but ultimately supported the levy. Republican Governor John Kasich, an ed-reform devotee, wants to make the Cleveland levy a model for the rest of the state.

Oregon: Voters approved Measure 85 (59.9 to 40.1 percent), a constitutional amendment that reallocates a tax rebate for corporations to K-12 education. Funding for the campaign came from three major public employee unions: the Oregon Education Association, the Service Employees International Union, and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. The vote deals with an oddity in Oregon’s income tax system: if tax revenues for a budget cycle exceed earlier projections by more than 2 percent, the “surplus” is returned to individual and corporate taxpayers rather than saved or used for other public purposes. Most of the corporations getting the rebate—called the “kicker”—have headquarters outside Oregon. The popular individual kicker remains in place, but state economists don’t expect there to be one until 2017.

South Dakota: In a veto referendum, voters defeated Referred Law 16 (67.23 to 32.77 percent), a reform package that shifted power from local school boards to the state, phased out continuing contracts and job protections for teachers, and mandated a statewide evaluation system and merit bonuses, both based largely on student test scores. The bill—some twenty-five pages long and, critics said, cobbled together—was unfunded when lawmakers passed it. The South Dakota Education Association led the campaign to put the law on the ballot and defeat it.

Washington: Voters approved Initiative 1240 (50.73 to 49.27 percent), which will allow up to forty charter schools to open in the next five years. Until the vote, Washington was one of only nine states not to permit charters (the other eight are Alabama, Kentucky, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and West Virginia). Two aspects of this referendum stand out. First, Washingtonians defeated charter schools in three previous votes: 1996, 2000, and 2004. Second, charter proponents had to raise $10.9 million dollars this time to eek out their 1.5 percent win. Donors included some of the usual ed-reform hawkers: Bill Gates ($3 million), Alice Walton ($1.7 million), and Eli Broad ($200,000). Other top backers were Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen ($1.6), Jackie and Mike Bezos (parents of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, $1 million), Seattle-based venture capitalist Nick Hanauer ($1 million), and Connie Ballmer (wife of Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer, $500,000). Opponents of the initiative raised $708,871, just one-fifteenth of the winners’ total. Bill Gates also contributed $1 million to the signature drive to put the initiative on the ballot. Spending about $2.1 million and paying workers nearly $6 per signature, charter patrons amassed about 350,000 signatures in eighteen days.

The controversy in Washington might continue because State Superintendent of Public Instruction Randy Dorn is considering a legal challenge. The Constitution requires all public schools to be under his department’s jurisdiction, but charter schools, which are defined in the initiative as public schools, will be under the authority of a government-appointed commission. Dorn—a former teacher, principal, and executive director of the Public School Employees of Washington (SEIU Local 1948)—was elected to a second term as superintendent the same night that the charter school initiative squeaked through. He ran unopposed. The struggle for and against corporate-style ed reform is a complex tale.

Joanne Barkan is a writer who lives in Manhattan and Truro, Massachusetts. She grew up on the South Side of Chicago where she attended public elementary and high schools.

No comments:

Post a Comment